.

Authors: Eran Igelnik and Assaf Patir, Start-Up Nation Policy Institute

Editors: Assaf Kovo and Elior Bliah, Israel Innovation Authority; Uri Gabai, Start-Up Nation Policy Institute

Israel earned the moniker “Start-Up Nation” due to the success of Israeli startups that established their position in international markets by breaking new ground in a wide variety of fields. As a result, the number of exits and public offerings by Israeli startups reached unprecedented sums, with $26.8 billion in equity investments in 2021, significantly higher than in 2020.

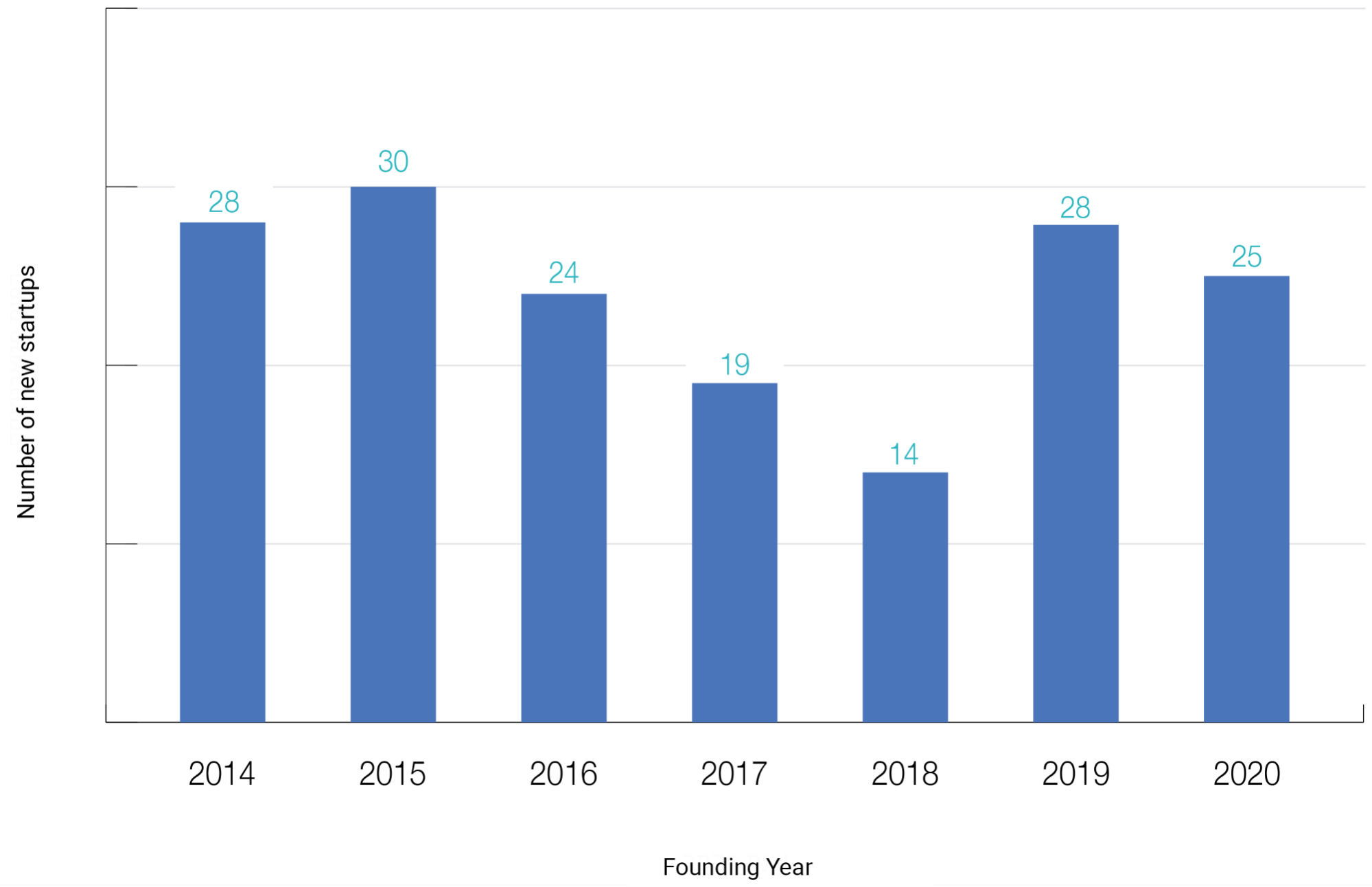

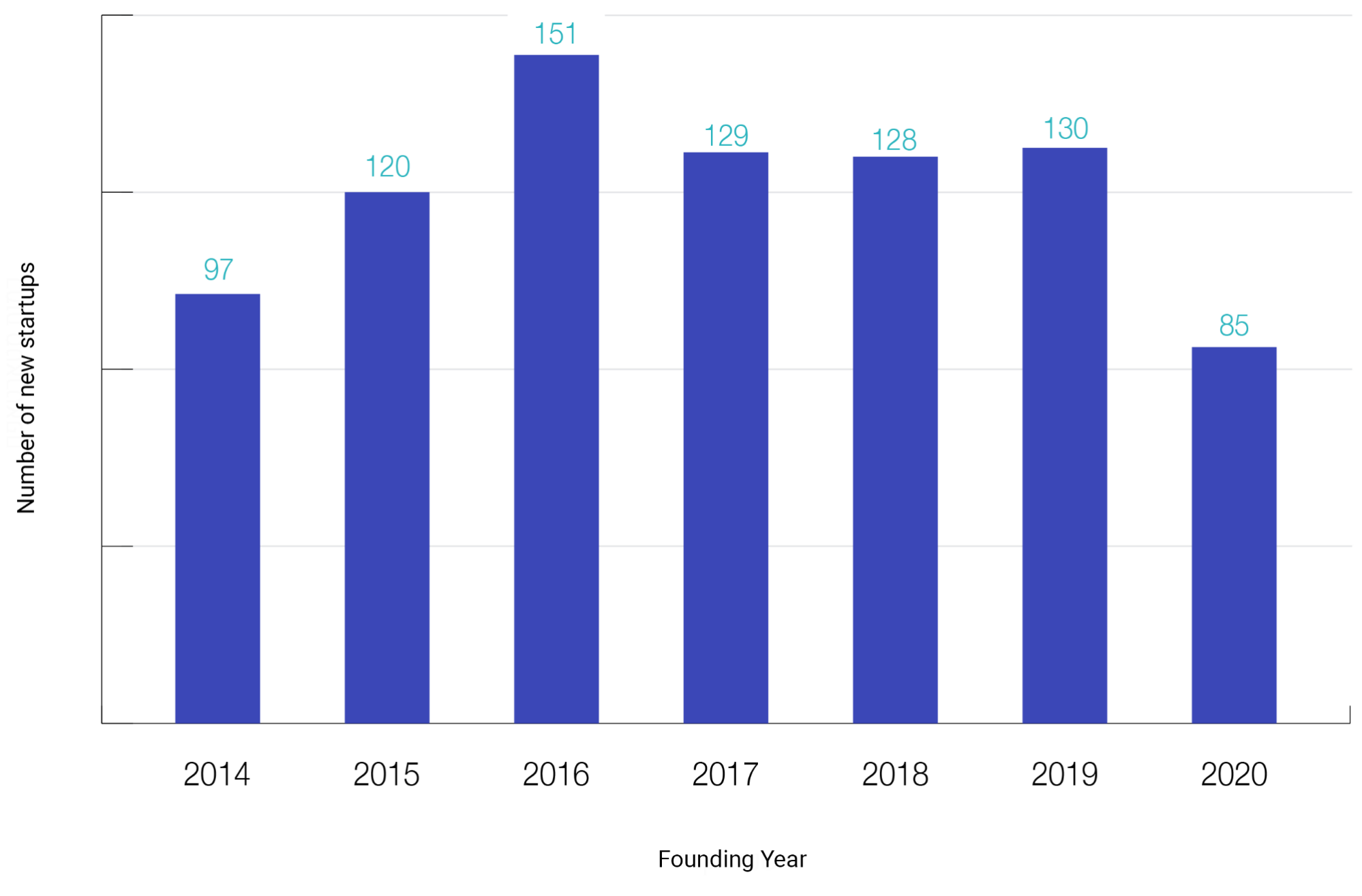

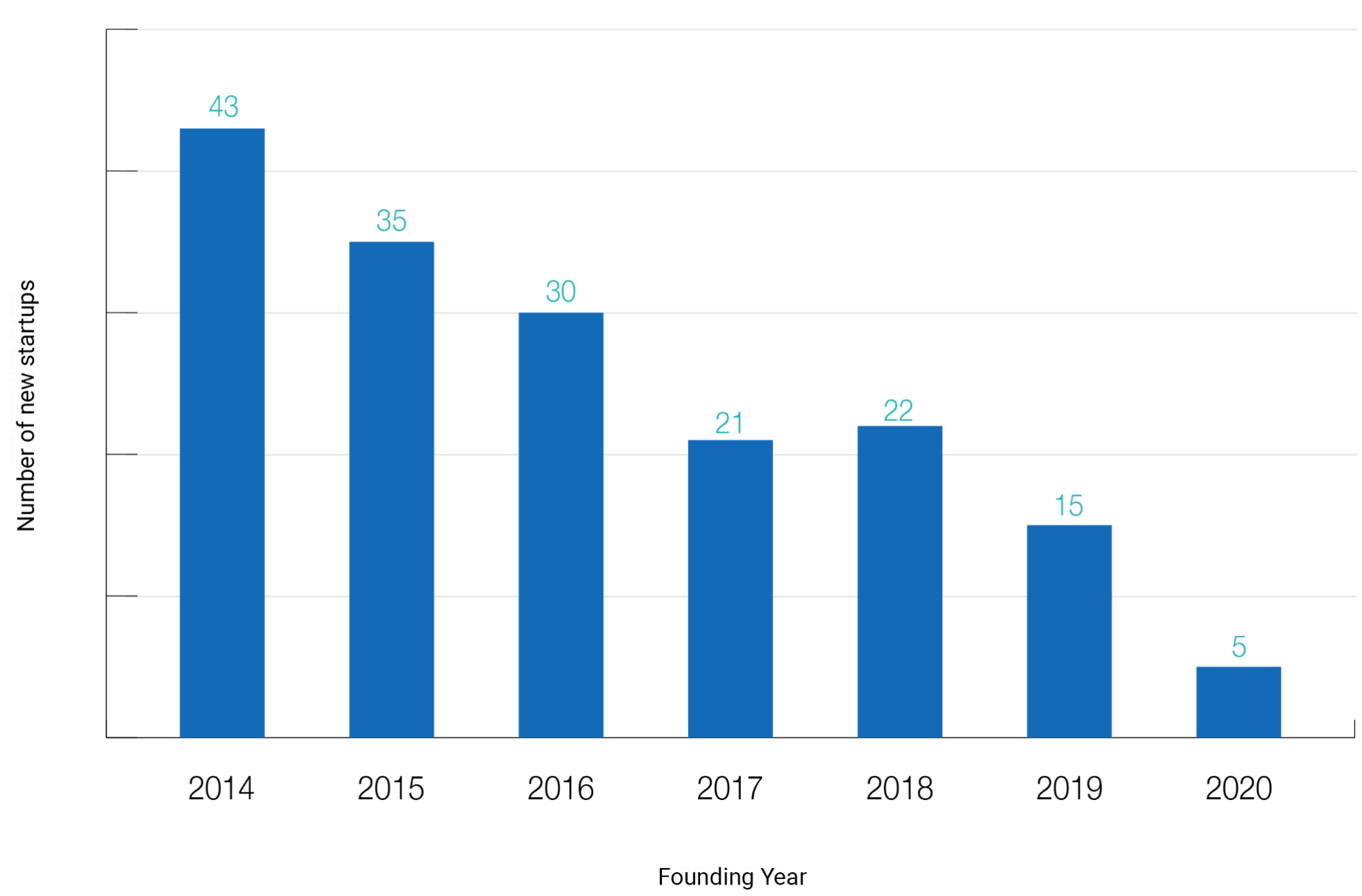

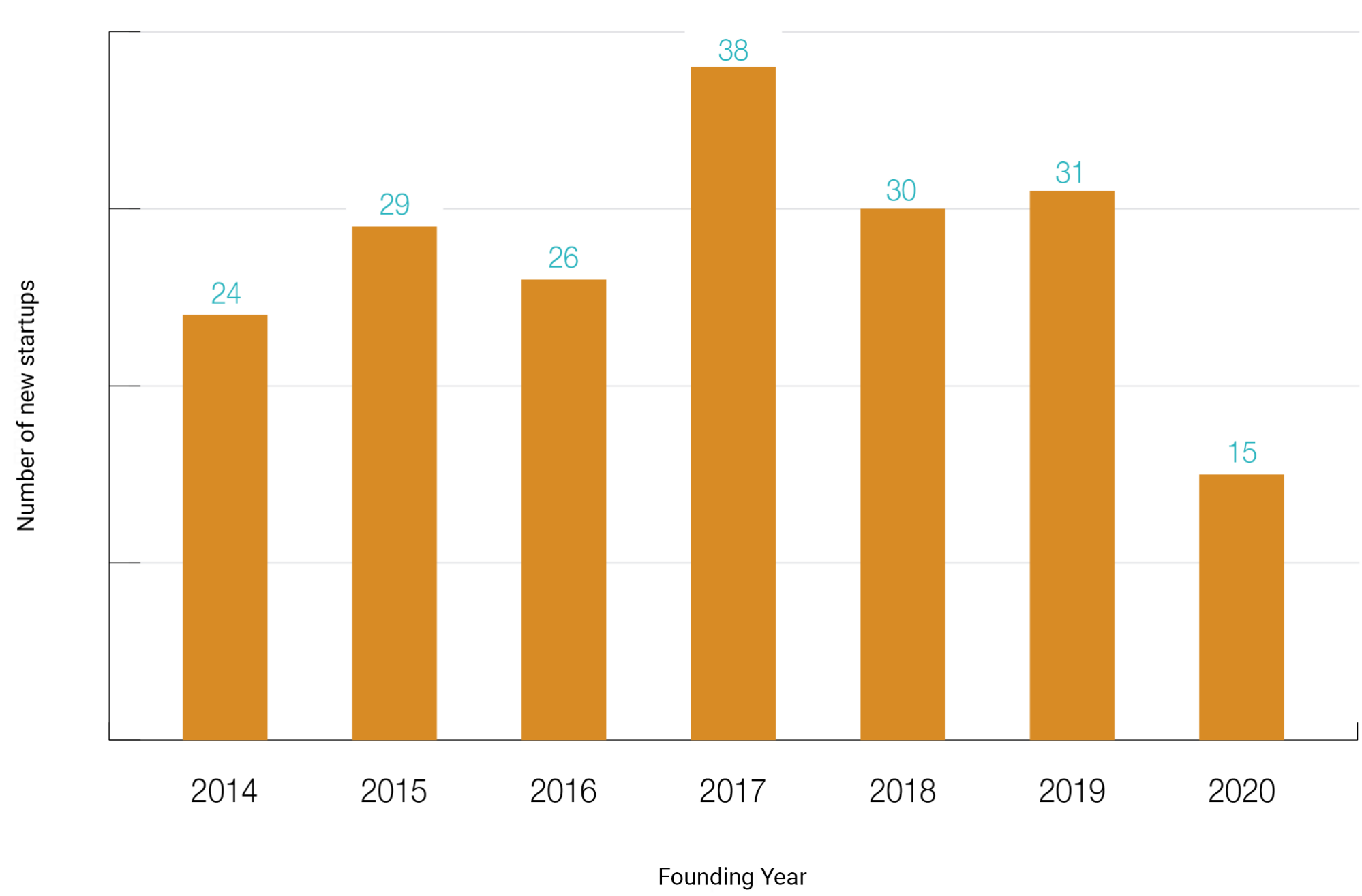

Still, there are signs pointing to a concerning trend. A report by the Israel Innovation Authority published in June 2021 presented a decline in the rate of new startups, beginning in 2014. Start-Up Nation Finder data show a similar trend, but beginning in 2017, with an annual decline of 14% (Figure 1).

The main goal of this paper is to propose possible explanations for this trend. In addition, we will discuss the significance of the phenomenon for the Israeli ecosystem and examine whether any government intervention is warranted at this stage.

The first part of the study presents empirical data related to the decline in the number of new startups. We then discuss the definition of high-tech companies and several issues that result from data collection methodologies. We then discuss different lenses with which the decline can be viewed and differentiate between sectors where this trend is more pronounced. We also compare the phenomenon to global markets to determine whether it is unique to Israel. At the end of this chapter, we test to see whether there are any indications for a change in the average quality of startups that can explain the lower rate of new companies established

The second part presents the main hypotheses for the decline in the number of new startups that arise from the data presented in part I. We evaluate three hypotheses:

The decline indicates an increase in startup quality; that is, in the past, more companies were launched but with a lower average probability of success.

Changing technological trends leading to the establishment of fewer but larger firms.

The proliferation of established Israeli tech firms and multinational R&D centers leads to fierce competition over resources, making it harder to launch new startups.

Finally, we discuss whether the decline in the number of new startups is a cause for concern and offer recommendations for when and how decision-makers should respond.

The research period: The current study focuses on the years 2014-2020. We did not include 2021, as the data for this year is still partial. We included 2020 despite being unusual due to the COVID-19 pandemic, as most of our analyses indicated that 2020 simply continued trends of previous years. Nevertheless, one should keep in mind that some of the observations for this year can be partially explained by the unusual circumstances.

The definition of the high-tech industry: Lacking a standardized definition for a tech company, different entities use different definitions. In addition, there is often a delay in receiving information on the establishment of new startups, and therefore it is important to ensure that the decline is not a matter of changing definitions or a bias in the data. To test this, we considered several possible criteria and factored in the time-lag. As will be shown, the decline is evident under several alternative definitions.

Different methodologies for measuring the number of new startups

In this report, we will refer to companies that appear in the Start-Up Nation Finder database as the population of tech companies. Despite different institutions using different definitions, the general trend of a decline in the number of new startups arises from both IVC data and data from the Central Bureau of Statistics. In addition, since Start-Up Nation Finder criteria have been consistent over the years, the actual definition should have no impact on the trend.

Similarly, the timing relating to the point at which an idea becomes a startup is open to interpretation. In many cases, entrepreneurs begin conducting business activity before registering with the Registrar of Companies. In order to supply as up-to-date a picture as possible, data collection for Start-Up Nation Finder is conducted with additional tools (i.e., LinkedIn) and not just by tracking the official Company Registry. This leads to a situation in which some startups on Start-Up Nation Finder are included before their official registration and they occasionally cease to operate before registering as well. Nevertheless, this distinction should not impact the overall trend: the rate of registered companies among all companies in Finder has remained constant (75%) over the years, and the rate of their decline is similar to the data presented above, as can be seen in Figure 2.

In addition, it is important to consider the delay in data collection. As mentioned above, data collection for the Finder database is based on several sources, and the information on the establishment of a new company is typically recorded in the database several months to years later (the average is 14 months, with a 6-month standard deviation).

As a result, estimates of the number of companies established each year will be downwards biased. To correct for this issue, we adjusted the number of companies established each year by estimating the gaps from previous years’ data (see appendix). Figure 3 shows that after this correction, the decline in the number of startups launched between 2017 and 2020 is indeed attenuated, standing at an average of 7% annually (compared with 14% before the correction).

Startups represent a wide range of technologies and sectors. Accordingly, the startups launched every year were examined based on Start-Up Nation Finder's sector criteria. The database classifies Israel’s technology industry into thirteen sectors according to the field in which companies operate and the products they develop (see appendix, Figure 11). When we examined the decline by sector, we found that it follows a similar trend in all sectors, except for two.

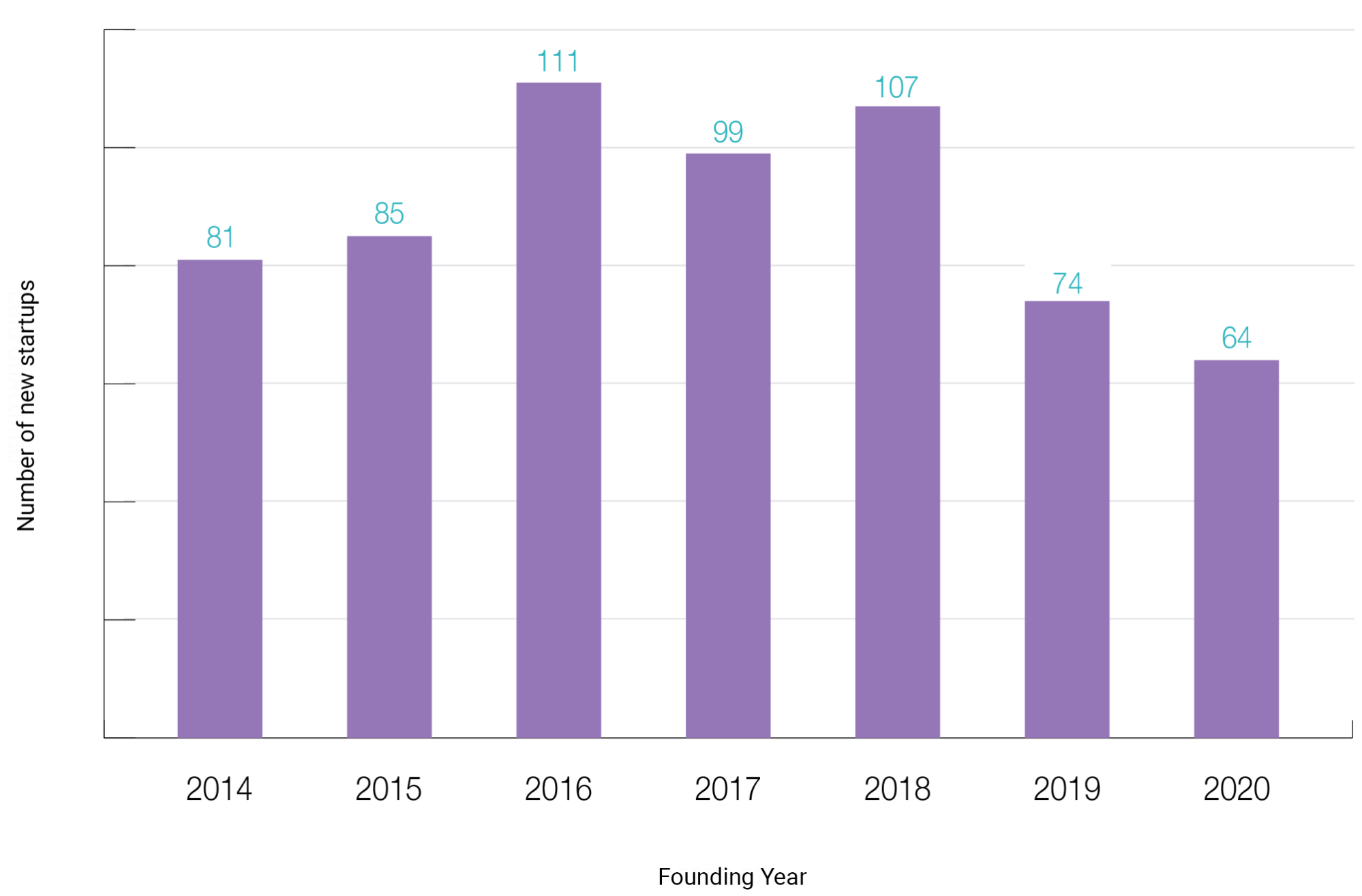

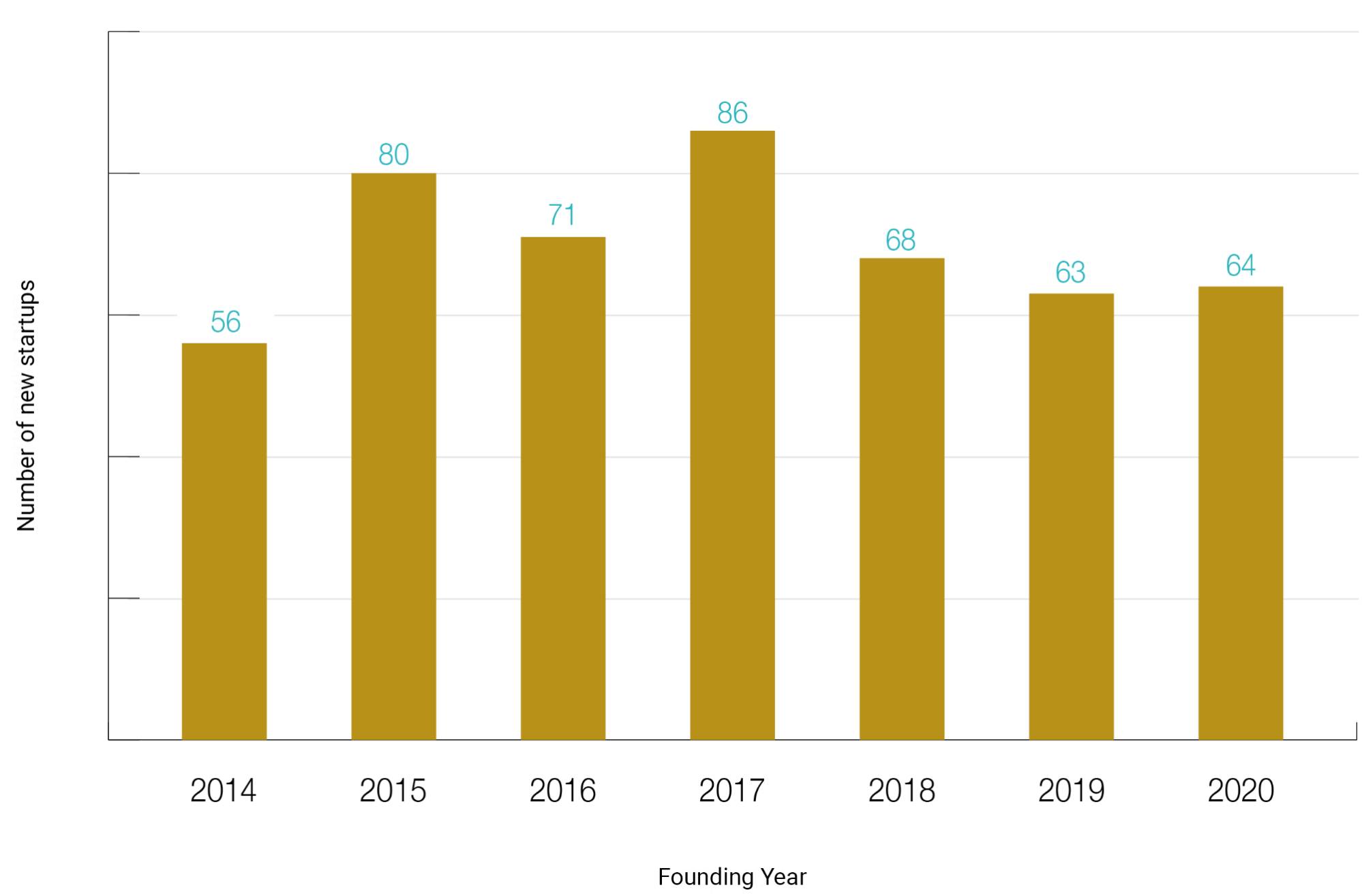

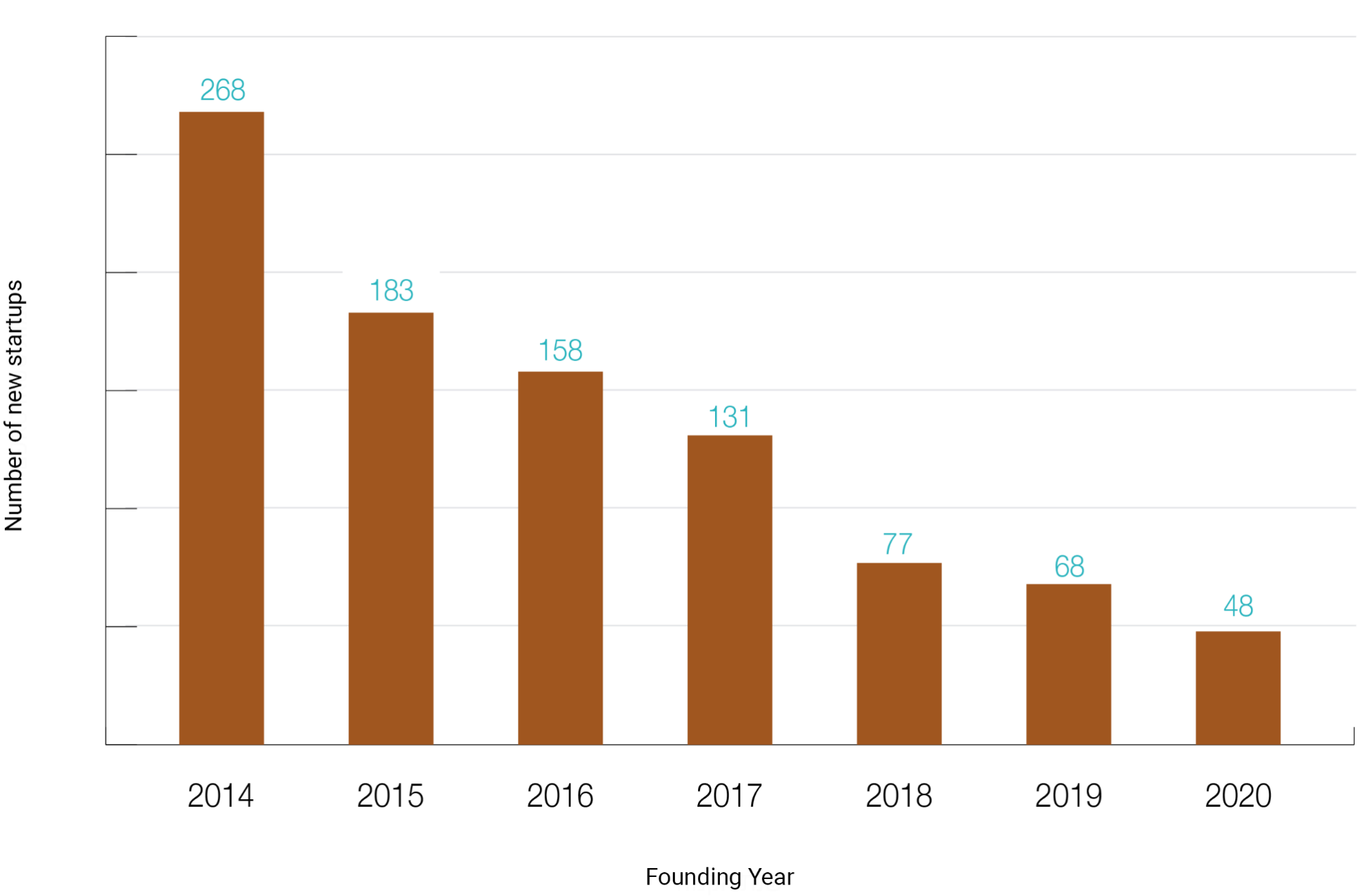

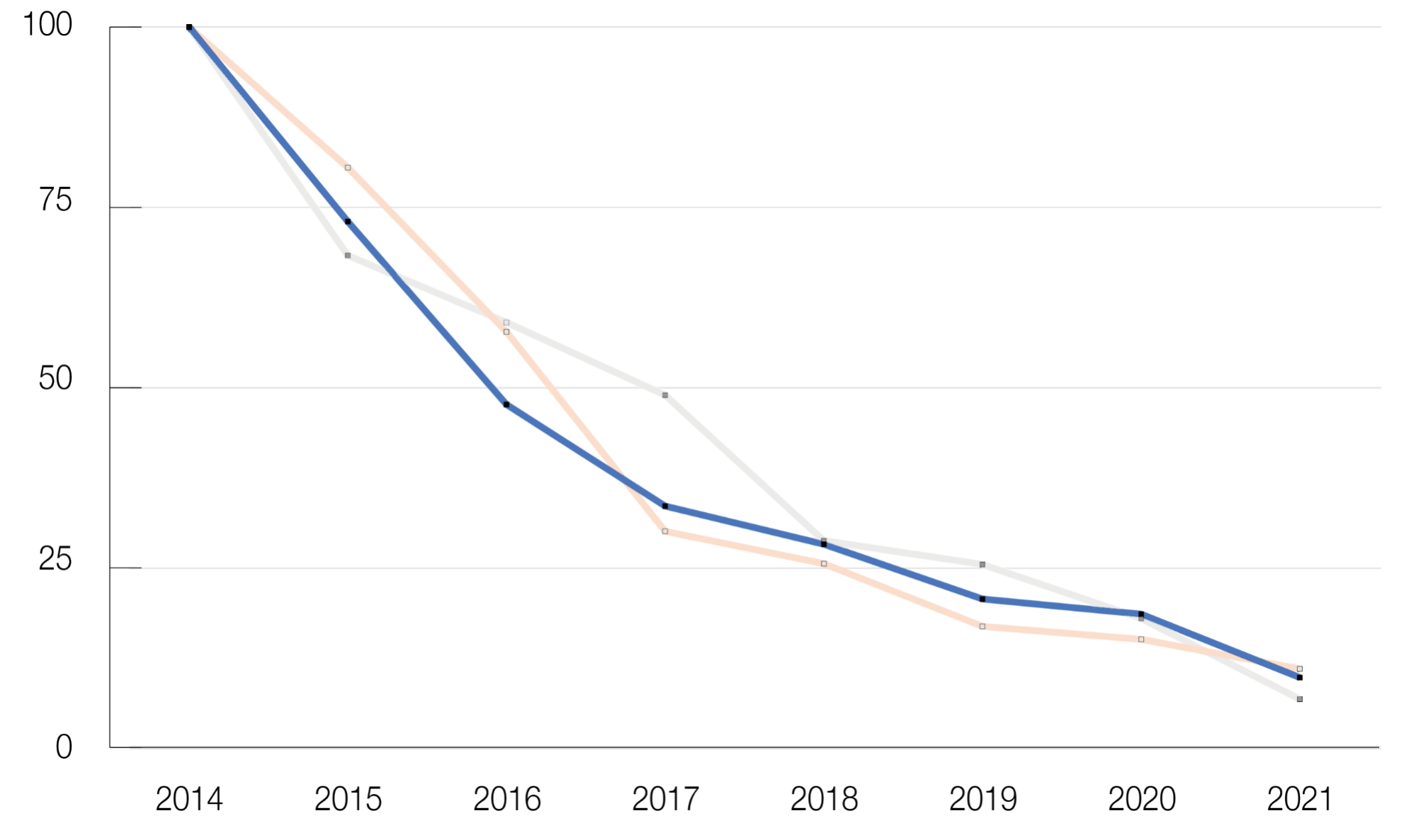

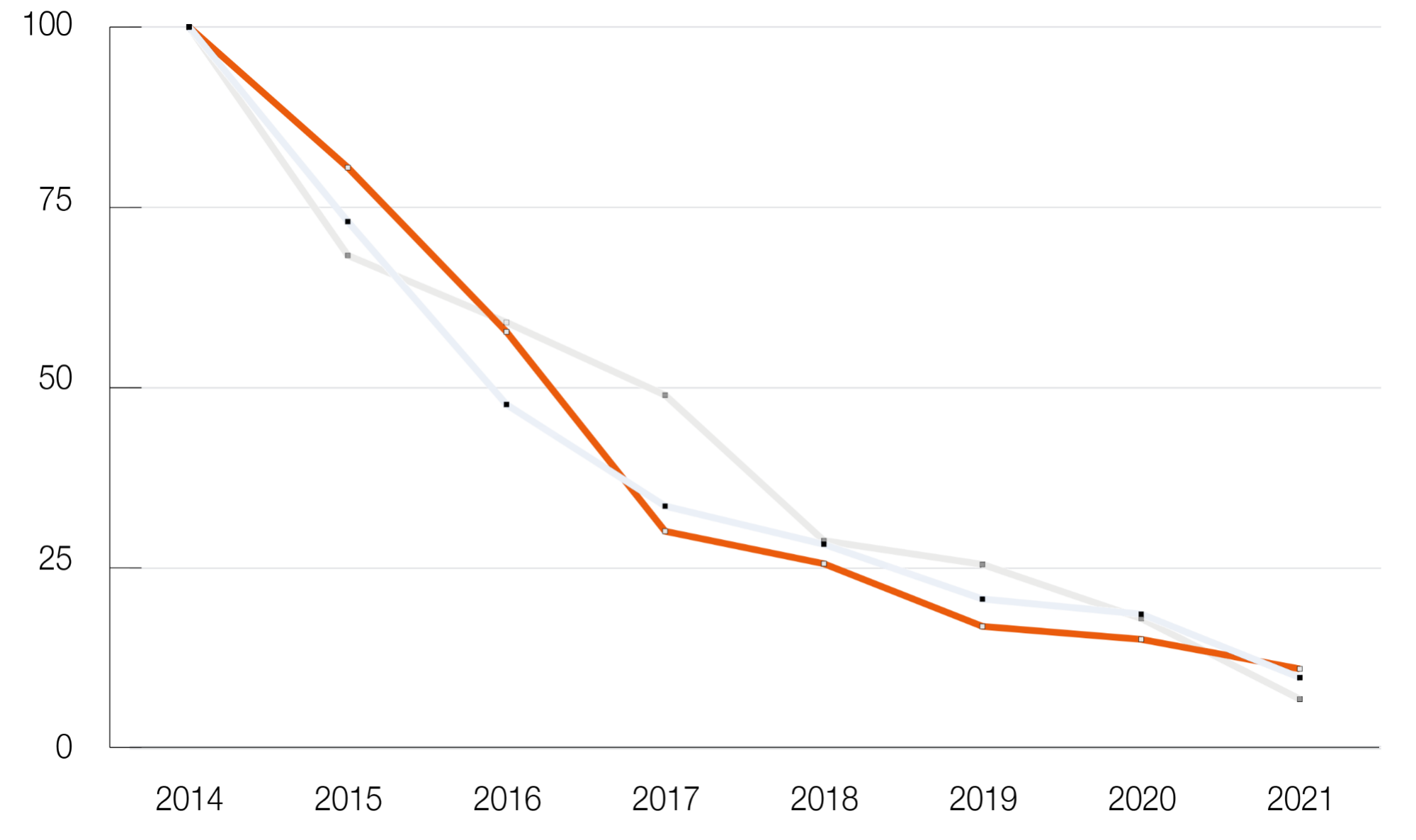

The first sector is Social Media and Advertising (hereinafter, SMA), which was responsible for a quarter of new startups established in 2014, but has since been on the decline. As mentioned above, the trend was noted starting in 2014 (note that Start-Up Nation Finder started operating in 2014, thus information on earlier periods is partial), and while the general decline only began in 2017, in SMA it started two years prior. Examining a wider time frame showed 2014 to be a record year in the number of new companies established in this sector. Figure 4 shows the establishment of new startups in this sector over the years. When comparing the gap between the number of startups established in 2019 and the number established in 2014 (200), it appears that the decline in this sector accounts for70% of the entire decline in those years (282). Figure 5 shows the decline described in this sector, compared with the decline in companies in all other sectors, with 2014 as the baseline year.

The second sector with a more acute decline was Fintech and E-commerce, averaging 50% over the last two years. That said, the limited time period, as well as the aforementioned time-lag, makes it difficult to assess whether this is a real trend or an isolated phenomenon.

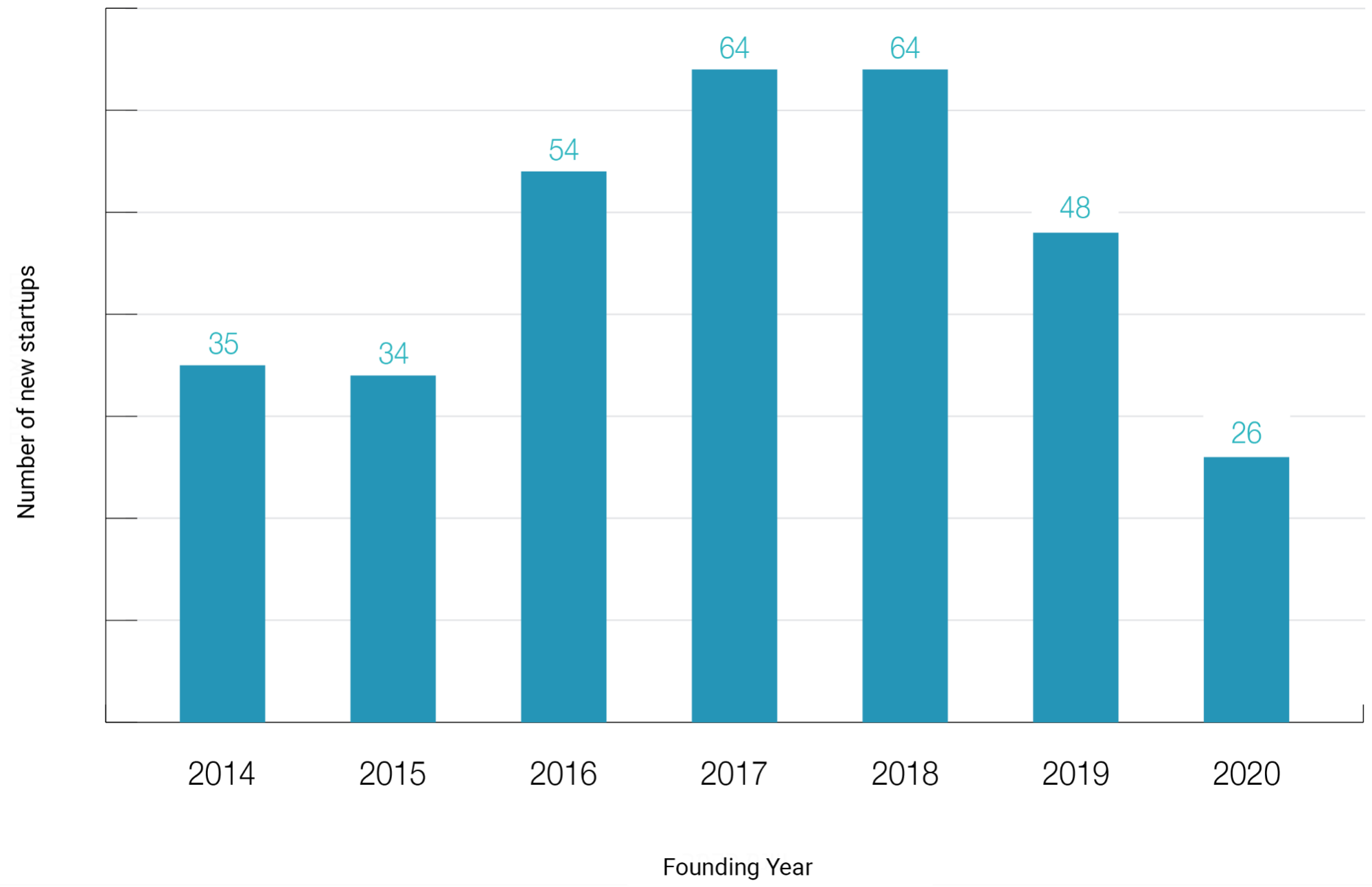

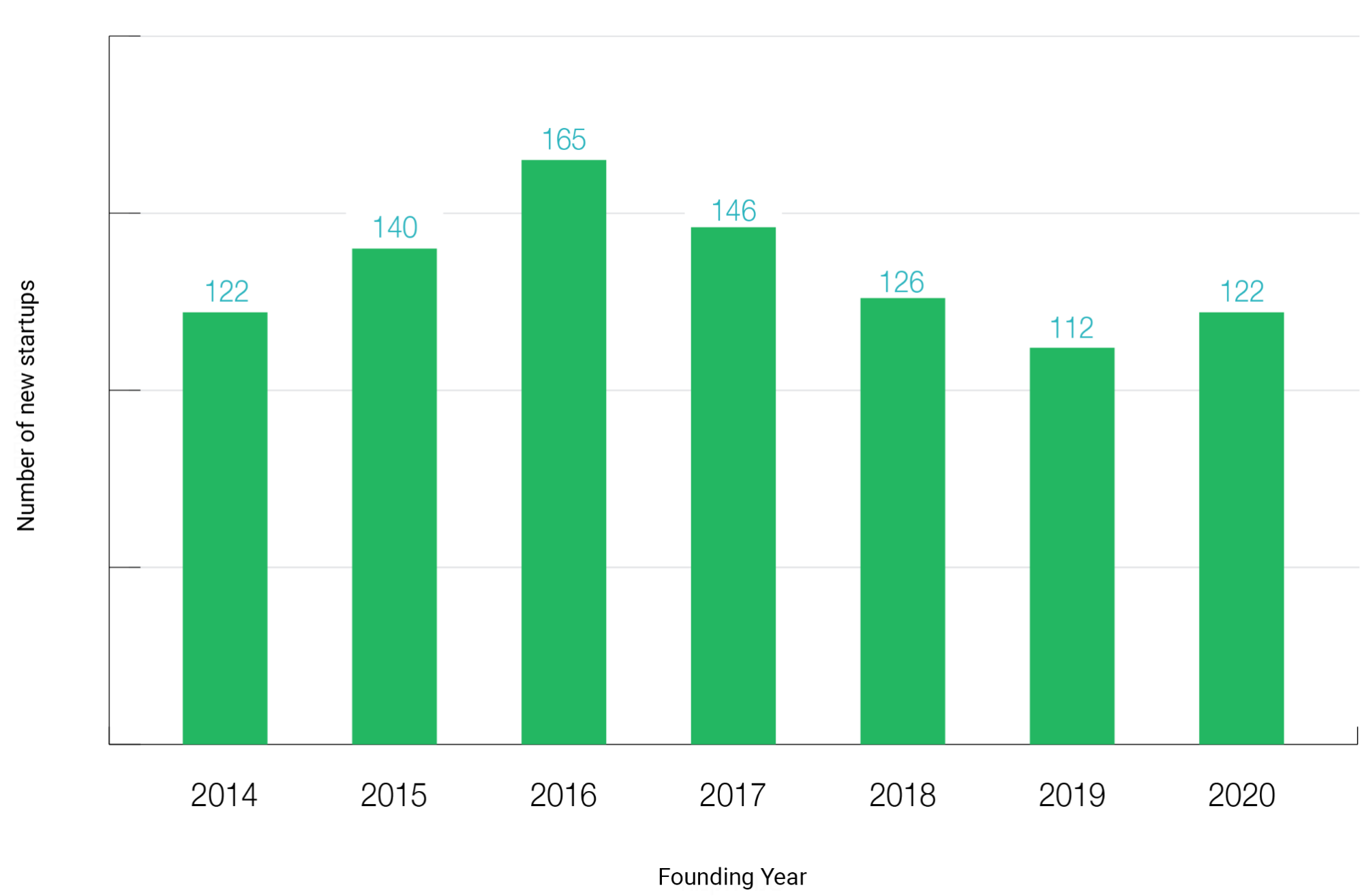

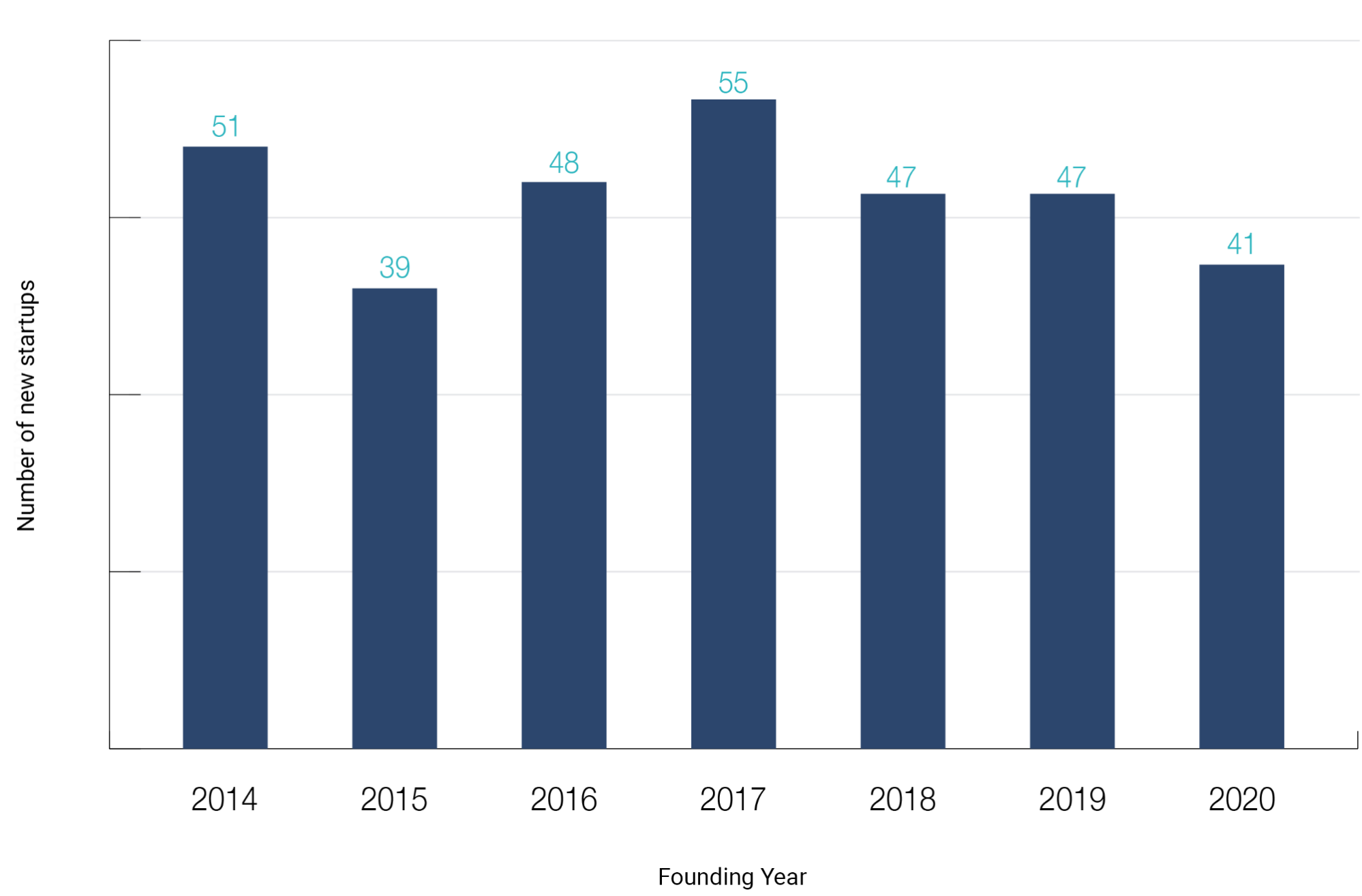

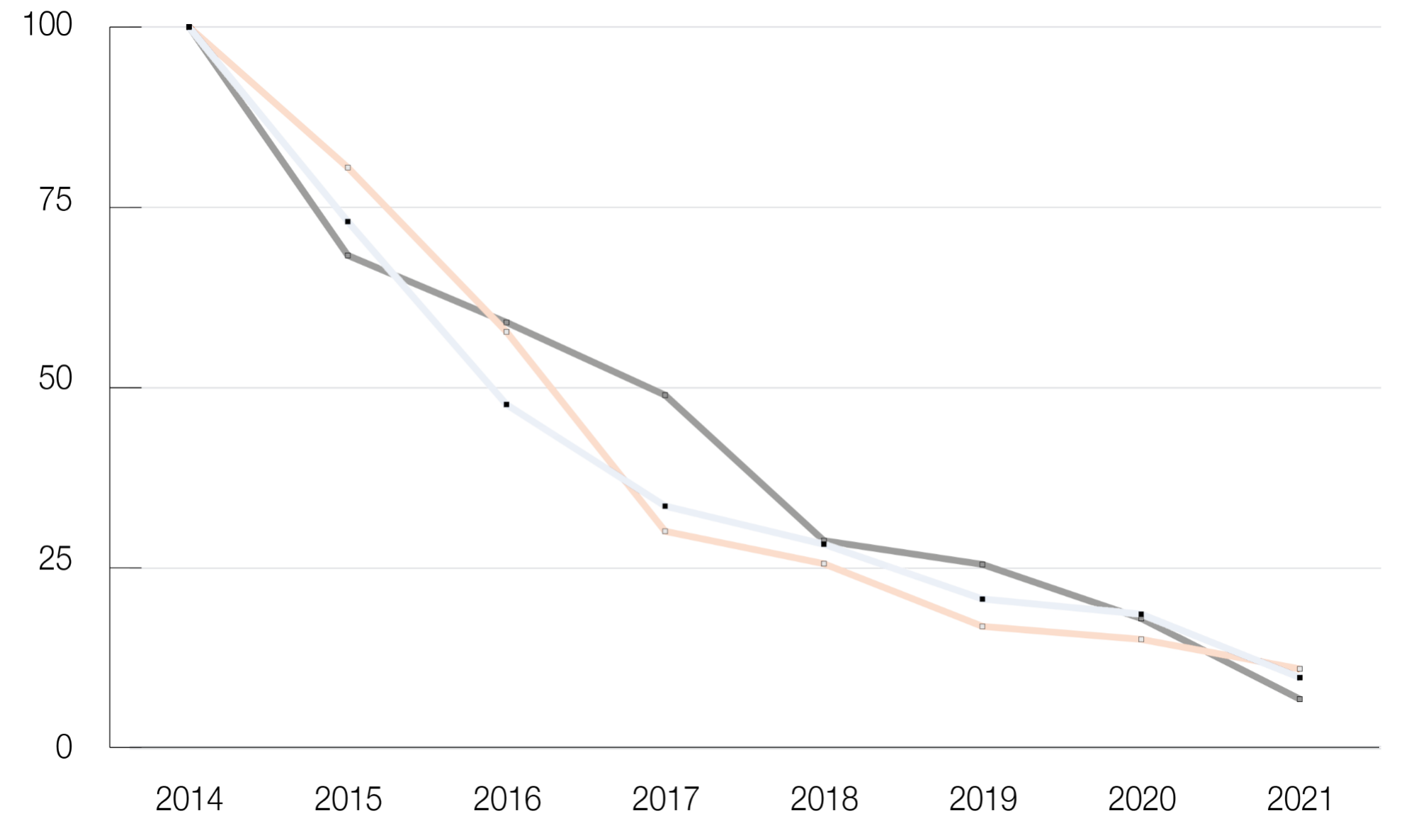

An additional analysis was conducted to determine whether the decline in the number of new startups was unique to Israel. We chose two leading ecosystems for comparison – Silicon Valley and London. As data from these markets is not available on Start-Up Nation Finder, we examined the companies’ establishment dates on PitchBook. Figure 6 indicates a downtrend in both ecosystems, albeit at different rates: 5% in Silicon Valley and 15% in London (compared with 14% in Israel). It is important to note that due to the databases’ differing methodologies, it is difficult to compare data in absolute numbers. Therefore, Figure 7 shows the data with 2014 as the baseline year. It is clear however that the decline in Israel is – at least partially – part of a global trend.

Figure 7: SMA compared to other sectors

Founding of new startups - 2014 = 100

We examined whether the decline in the number of new startups indicates an improvement in investors’ capacity to identify successful ideas, and alternatively, to avoid less successful ones. While the best measure for the quality of a company is the return on investment (ROI), financial data for private companies is often unavailable, thus such a comparison is not feasible. Furthermore, for startups established several years ago, data related to profitability or market valuation is often overly influenced by market volatility and therefore is not useful for this comparison.

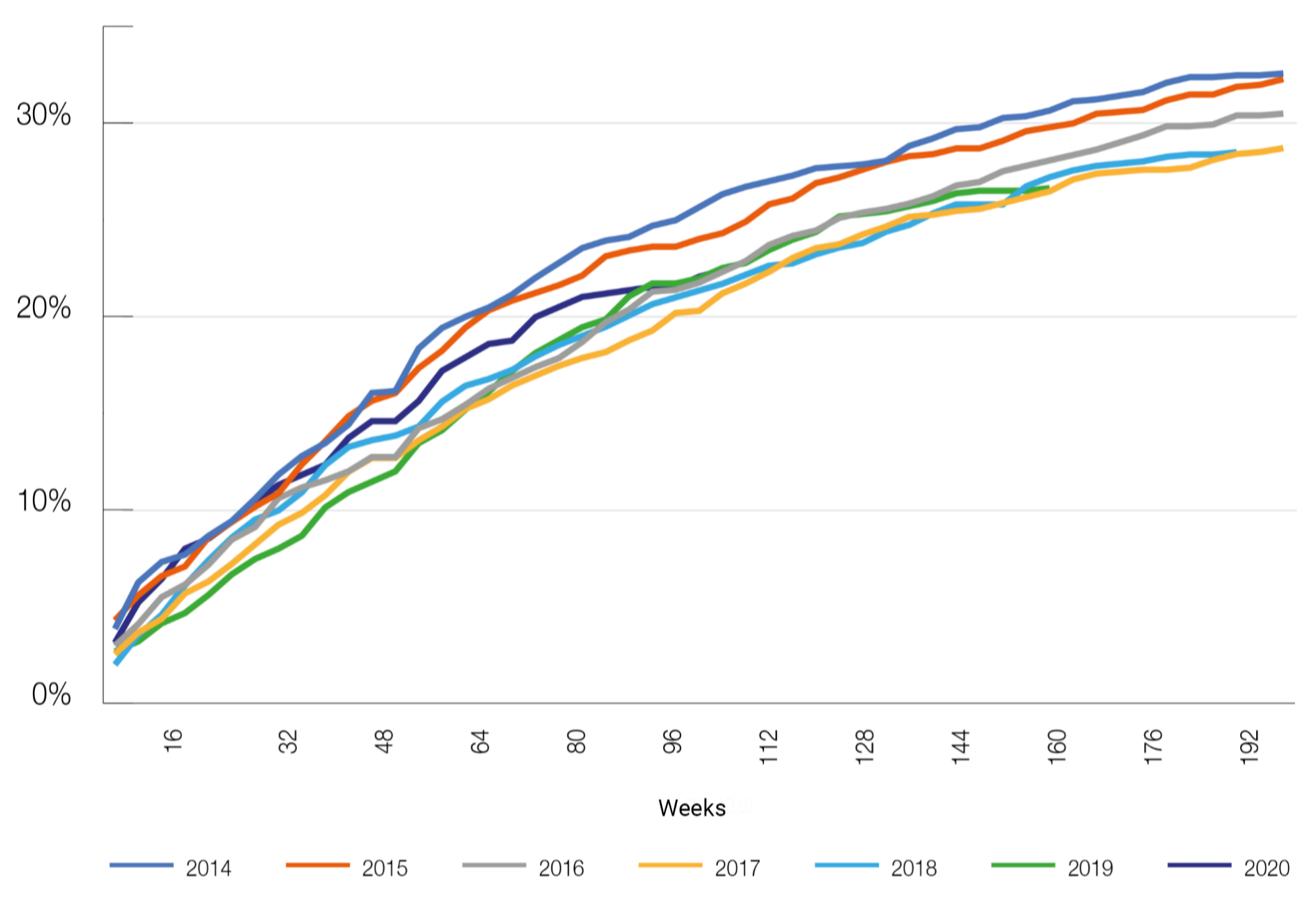

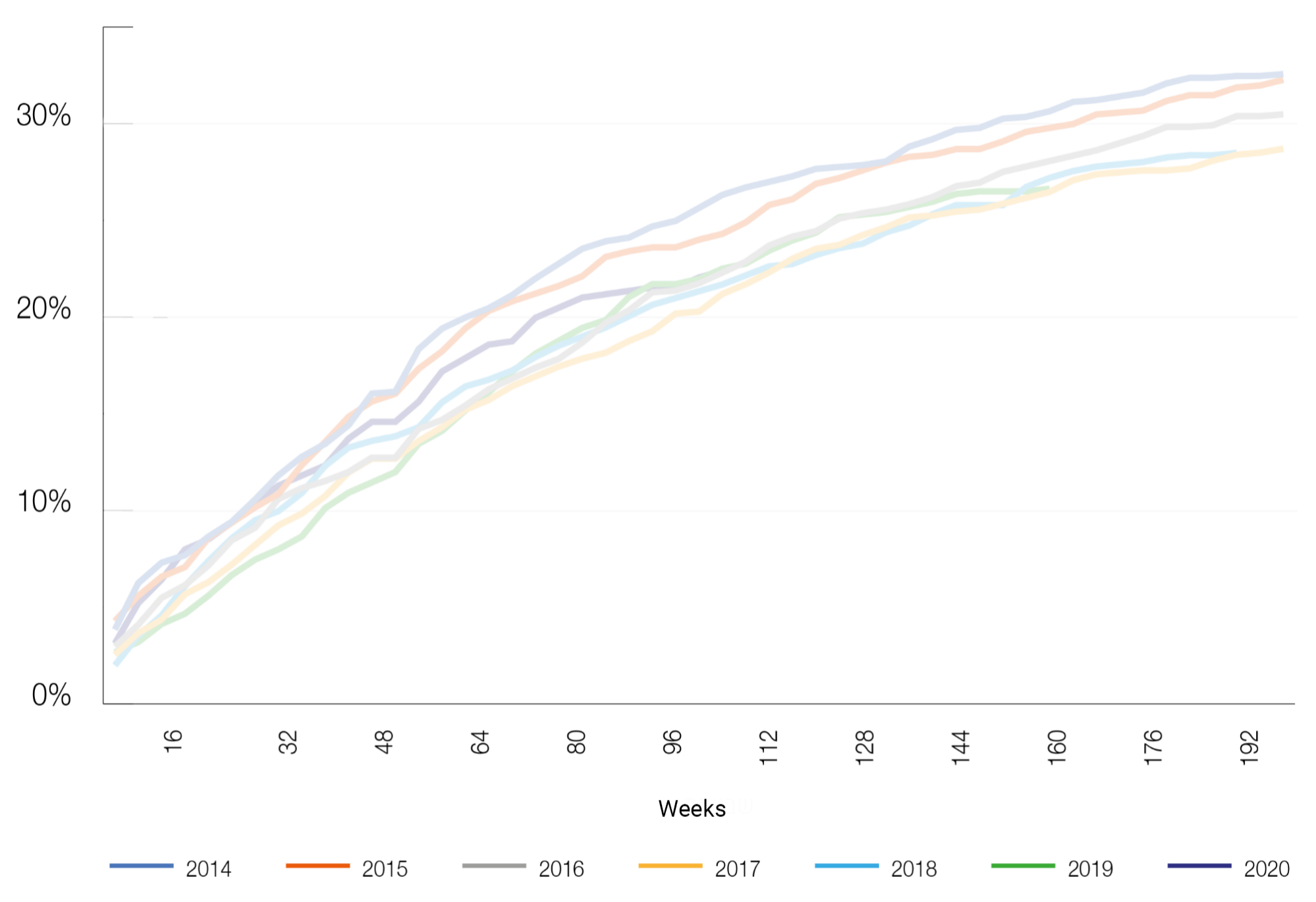

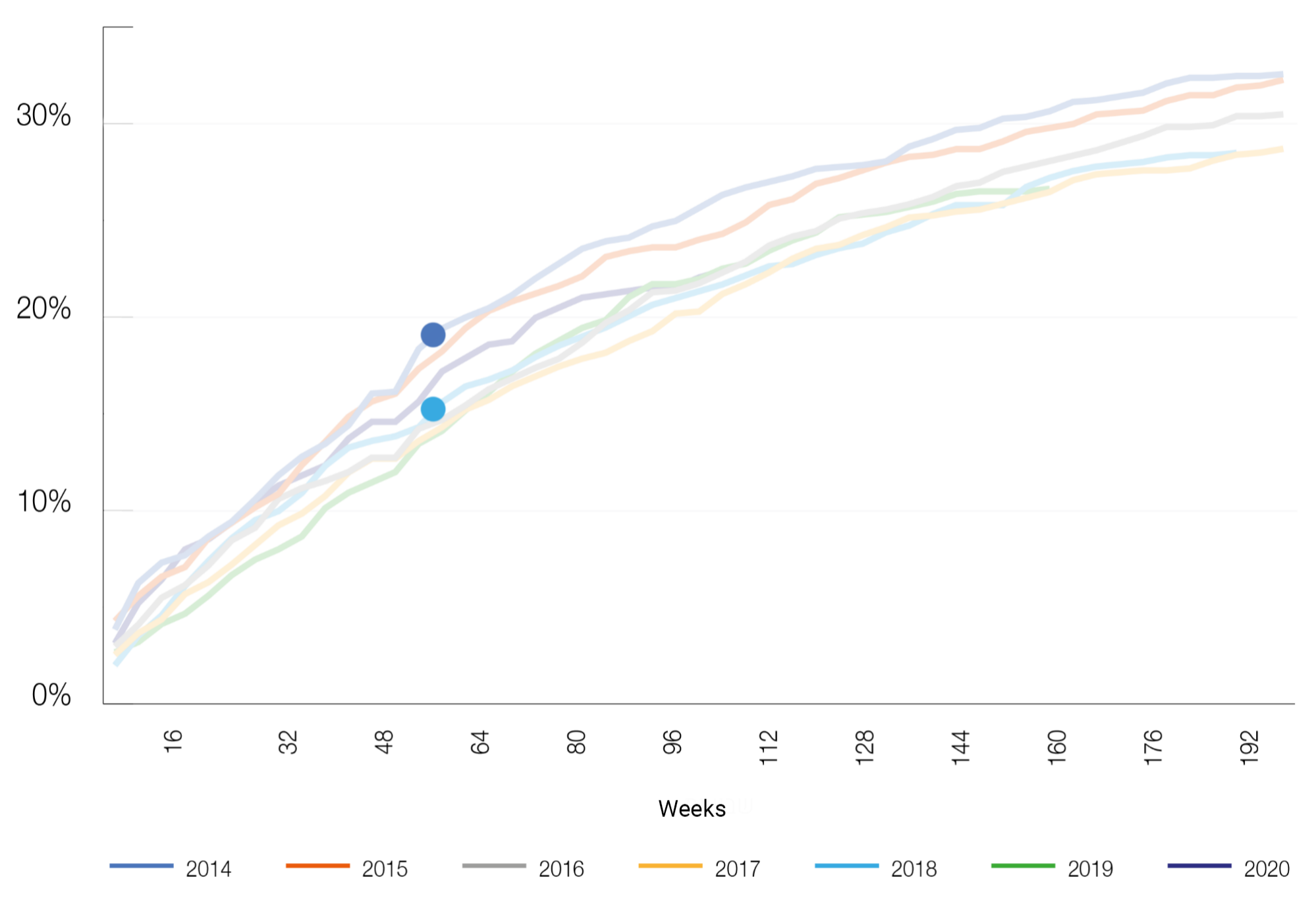

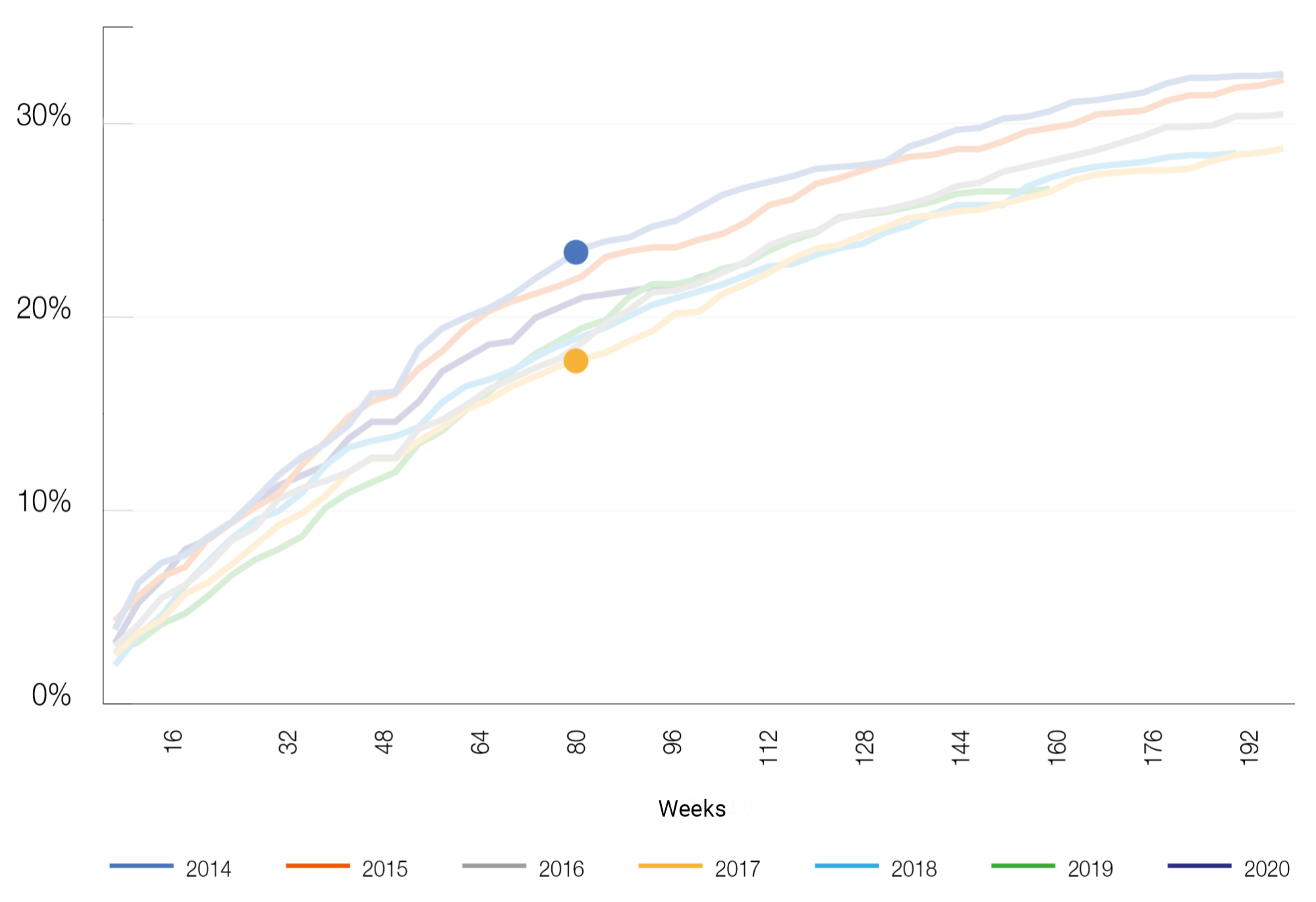

As an alternative, we used the ability to raise funds (seed funding and above) within a given span of time as a proxy for success. In other words, for every point in time, we took the percent of companies within a cohort (based on year of establishment) that managed to raise such funding. This method gives us investors’ subjective assessment of a startup’s chances for success.

The figure presents the results. The x-axis shows time in weeks and the y-axis shows the proportion of companies in a cohort that succeeded in raising funds by that point in time (in other words, the cumulative percentage of companies that raised funds by that time).

For example, if we look at the 52-week point on the x-axis, we can see that 14% of companies established in 2018 secured funding within a year of being established, while 18% of companies established in 2014 managed to do so within the same amount of time. Another

Another example is the point at which the distance between the lines is greatest. We found that after 80 weeks, while 24% of the companies established in 2014 succeeded in raising funding, only 18% of companies established in 2018 succeeded in doing so.

We examined whether the decline in the number of new startups indicates an improvement in investors’ capacity to identify successful ideas, and alternatively, to avoid less successful ones. While the best measure for the quality of a company is the return on investment (ROI), financial data for private companies is often unavailable, thus such a comparison is not feasible. Furthermore, for startups established several years ago, data related to profitability or market valuation is often overly influenced by market volatility and therefore is not useful for this comparison.

As an alternative, we used the ability to raise funds (seed funding and above) within a given span of time as a proxy for success. In other words, for every point in time, we took the percent of companies within a cohort (based on year of establishment) that managed to raise such funding. This method gives us investors’ subjective assessment of a startup’s chances for success.

The figure presents the results. The x-axis shows time in weeks and the y-axis shows the proportion of companies in a cohort that succeeded in raising funds by that point in time (in other words, the cumulative percentage of companies that raised funds by that time).

For example, if we look at the 52-week point on the x-axis, we can see that 14% of companies established in 2018 secured funding within a year of being established, while 18% of companies established in 2014 managed to do so within the same amount of time. Another

Another example is the point at which the distance between the lines is greatest. We found that after 80 weeks, while 24% of the companies established in 2014 succeeded in raising funding, only 18% of companies established in 2018 succeeded in doing so.

Start-Up Nation Policy Institute is an independent think-tank that works to strengthen the Israeli innovation ecosystem through research and policy recommendations. The Institute works in partnership with the public sector and the high-tech industry to advance policies that maintain Israel’s technological edge and expand Israeli innovation to all areas of its economy & society. The Institute is part of the Start-Up Nation Central group and is fully funded by philanthropy.

The Israel Innovation Authority is a statutory public agency in charge of Israel’s innovation policy, established in 2016 based on the activity of the Chief Scientist at the Ministry of Economy. The authority advances innovation as a lever for sustainable and inclusive economic growth out of a view that innovation is the most significant engine of growth for the Israeli market. The authority works to strengthen the infrastructure of Israel’s economy of knowledge, while continually examining the obstacles and opportunities presented by Israel’s innovation ecosystem. The authority gives entrepreneurs and innovation-leaning companies in Israel a variety of funding and other instruments to help them deal with the changing needs of the modern world of innovation. The social-public department in the authority leads activity to increase the size of human capital available for the tech industry.

Cleantech

Agro and Food Technologies

Software Applications

Security and Safety Technologies

Consumer Electronics

Digital Health and Medical Technologies

Education and Knowledge Technologies

Industrial Technologies

Fintech and eCommerce

Enterprise Solutions

Mobile and Telecom Technologies

Pharmaceuticals

Social Media and Advertising

Fig. 12 shows the details of new startup launches around the world as they are given by PitchBook. As was mentioned in the study regarding Silicon Valley and London, it is impossible to make an absolute comparison of the number of companies between platforms, due to differences in defining the threshold criteria of each platform.